NO INDUSTRY IS AN ISLAND:

UNDERSTANDING INTERNATIONAL BUSINESS THROUGH VALUE NETWORKS AND MARKETING RESEARCH

Network research pioneer Kristian Möller had a eureka moment up in the air

A simple and logical way to categorise business networks was born during a flight.

On a flight to Stockholm in 2001, Kristian Möller, then a professor of marketing at the Helsinki School of Economics, was outlining a solution to a difficult problem with pen and paper. What would be a logical and simple enough way to categorise business networks?

‘After sketching for a while, I saw the solution right in front of my eyes – and it was even simpler than I had thought,’ Professor Emeritus Möller recalls. Möller had become interested in network research a few years earlier. It challenged the mainstream view in marketing research, which saw businesses as merely part of the faceless market, with competition the only driving force behind development. Network research, on the other hand, emphasised the relationships and cooperation between businesses.

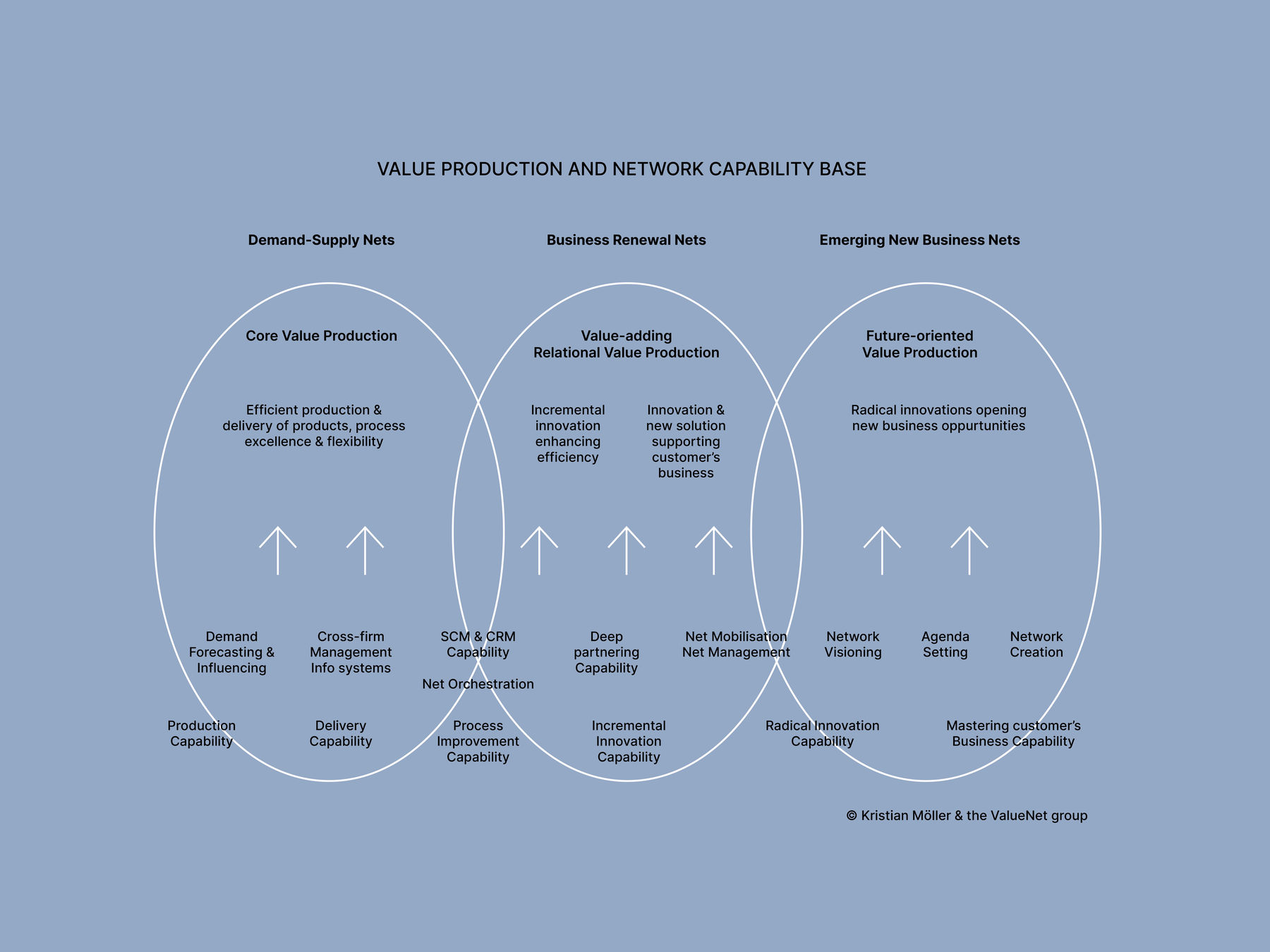

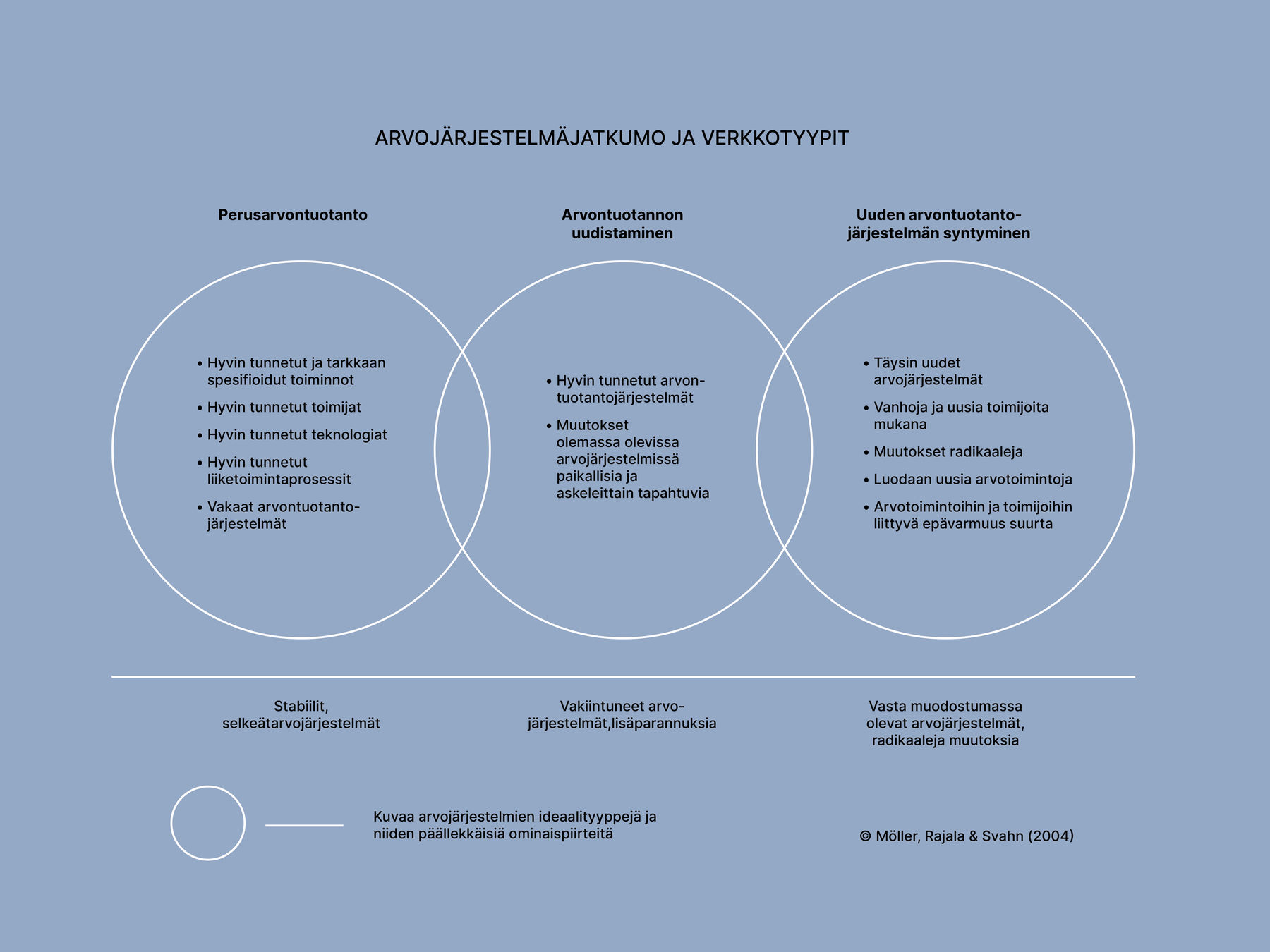

During the flight, Möller realised that networks can be placed on a continuum according to how precisely defined their value creation logics and value activities are. Do they have well-established products, partners, technologies and processes? Are they still developing these, or are they somewhere in between?

‘At the left end of the continuum are well-established business networks. The main company in the network is like a symphony conductor, directing the members of the orchestra. The musicians – that is, the partners, suppliers, distributors and core customers – are virtuosos in their own fields. The business networks of Toyota and Ikea are prime examples of this,” Möller says.

The networks at the right end of the continuum can be compared to a new music genre, he says. Just like a new music style, a technological innovation has to break through, and the developer must be able to mobilise partners and investors. There’s a lot of uncertainty in these kinds of innovation networks. There’s also the risk that the network will be unsuccessful, meaning that the innovation fails to take off.

Networks at the middle of the continuum are concerned with the gradual renewal of the value creation process. Multiparty project networks are typical, tasked with improving the established value network, its business processes, and product and service offerings. This logic is also followed by large-scale construction projects and systems design.

Boosting, envisioning and inspiring

After the breakthrough, Möller and his colleagues focused on network management research. ‘Different types of networks have to be managed in different ways,’ he says.

In established networks, the main company must be able to boost the entire network and leverage a strong brand to attract desirable partner companies to the network. In innovation networks, the focus is on the ability to envision and create development agendas and engage skilled partners.

Several research groups have grown up around the network research carried out at the Helsinki School of Economics (HSE), which merged with two other universities to form Aalto University, and at other Finnish universities. The topic has spawned dozens of dissertations and scientific articles, and Finland has become one of the top three countries in business network research.

The results of the research have been adopted both by businesses and public sector, thanks to university education and the wide-spread cooperation between research institutions and the business world.

Text by Anu Vallinkoski

Henrikki Tikkanen: These days, most businesses listen to their customers

An unprecedented survey has monitored the state of marketing for nearly two decades. A new research area at the Department of Marketing focuses on decision-making biases plaguing export companies.

In autumn 2022, the Department of Marketing at Aalto University’s School of Business will send out a survey to each Finnish company with at least five employees. The survey is part of the StratMark project launched in 2005, which monitors the state of marketing and the quality of marketing expertise in Finland.

‘The biannual survey has generated a time series that is unique on a global scale and has aroused wide international interest,’ says Henrikki Tikkanen, professor of marketing at Aalto University, who heads the project.

Many of the questions remain the same from one year to the next. They focus on how effectively businesses are able to monitor the impact of their marketing activities, among other things.

However, the survey also evolves over time. Next autumn, businesses will be asked to reflect on how COVID-19 has affected their operations. How have they used their marketing and customer expertise to address issues brought on by the pandemic?

The survey data acquired over the years has benefited Finnish businesses. Several researchers from the project have also moved into the business world to work on developing methods for measuring marketing impact.

‘Our research reveals how marketing in Finland has evolved in the 21st century. Businesses are significantly more customer-oriented than before. Now, the majority of Finnish companies listen to their customers, monitor their competition, and share customer data within the organisation,’ Tikkanen says.

From biased decisions to the best options

The Aalto University Department of Marketing also studies the mechanisms underlying the decisions leading to action.

Associate Professor Sanna-Katriina Asikainen, who focuses on international marketing, is investigating how cognitive distortions affect decision-making at export companies. A good example of distorted thinking is the status quo bias, according to which people tend to favour the existing way of doing things.

Asikainen and her colleagues have studied the impact of bias using an experimental setup in which export directors from the participating companies decide on a hypothetical entry to a new export market. The experiment includes one solution that is theoretically the best and will most likely lead to a successful conclusion.

When the status quo bias applies, export directors are likely to go with the known and trusted solution, even when it isn’t the best option. When factors favouring the right choice are added to the setup, some directors give up their old ways.

‘Decision-making biases may have fatal consequences. Entry to a new market is a huge investment that often goes wrong,’ Asikainen emphasises.

Text by Anu Vallinkoski