ENGINEERING SAFETY AND SUSTAINABILITY AT SEA

A gigantic cruise ship split along the middle was born with the help of new calculation methods

Beginning in the 1990s, cruise ships started to grow into massive floating oases, which posed new challenges for engineering. At the Helsinki University of Technology (HUT) Marine Department, this launched the era of systematic structural research.

The Oasis of the Seas was launched at the STX Finland shipyard in Turku in 2009, and it revolutionised the cruise industry. The 65-meter-high vessel has an exceptional split-deck design, with the cabins in two towers and an outdoor central park with live trees and plants running down the middle.

HUT marine technology experts were involved in solving the architecture-induced challenges of the gigantic cruise ship in the late 1990s and early 2000s. This is a typical example of how research evolves in the field: a need arises in society or the industry, and advanced experts are called in to solve the grand challenge of maritime engineering.

Long tradition

Finland is often compared with an island because its exports and imports depend on shipping. No wonder then that marine technology has a long tradition at Aalto University.

Shipping and marine engineering have been shaped by, among other things, a method for judging the stability of ships created by Jaakko Rahola in 1939 and the ice class rules published in 1985. The ice class rules divide vessels into ice classes with different requirements for engine power and the strength of the hull and propulsion system. For example, ships calling at Finnish ports must conform to the Finnish ice class. The rules are meant to guarantee the safe operation of ships in different ice conditions, and they have been adopted around the world.

Researchers at HUT did pioneering work on calculating the pressure caused by ship-ice collision as early as the 1970s. In the 1990s, they developed new methods for calculating requirements for engine power and hull dimensioning.

‘Every winter for five or six consecutive years, one of our researchers was constantly onboard, taking measurements. As computer technology advanced, the computational models became more and more accurate,’ says Pentti Kujala, professor of marine technology.

In the 1990s, cruise ships became floating oases with lots of open space. Nevertheless, they needed to navigate safely amid the waves of the open ocean. Designing structural solutions for sun deck restaurants, loft cabins, and other facilities, or managing the vibrations caused by the waves would not have been possible without the development of new calculation methods.

Gradually, the focus expanded from single ship structures to how vessels interact with each other in different maritime areas. ‘We started to investigate how ships move in the Baltic Sea, what the collision risks are, and what kinds of damage could occur,’ says Jani Romanoff, professor of marine technology.

In marine technology, research is closely linked to training new experts. ‘Research and method development alone are usually not enough to enter the field. Businesses need experts with a strong theoretical background in using new calculation methods for demanding engineering applications,’ says Heikki Remes, who heads the Marine Technology research group.

Text by Terhi Hautamäki

New ships must withstand stronger storms and moving ice loads

Researchers at Aalto University are solving global marine technology challenges, many of which are caused by climate change. The developed engineering solutions utilize even artificial intelligence and behavioural sciences.

The list of requirements for the vessels of the future is long. Ships must be carbon-neutral, energy-efficient, and built from recyclable materials. At the same time, they must endure the increasingly high waves and strong storms caused by climate change. The changing conditions will make our understanding of ice and ocean waves obsolete. Addressing these challenges calls for foresight and collaboration between marine technology and meteorology.

‘Traffic is increasing in the Arctic and Antarctic Oceans. Although the volume of ice will decrease, it won't disappear. Ice will move more in the future. The interaction between the ice and waves is a new phenomenon,’ says Pentti Kujala, professor in marine technology.

Changes in seafaring create new requirements for the structure of ship hulls. For environmental reasons, they must be as light as possible, but they also have to withstand the extreme loads caused by storms and ice. Ship designs must guarantee their safety for decades to come, even in changing conditions.

Marine technology researchers at Aalto are hard at work investigating issues such as fluid-structure interaction and the fatigue strength of lightweight structures. Research is also needed to determine the safety of new low-emission fuels meant to replace diesel.

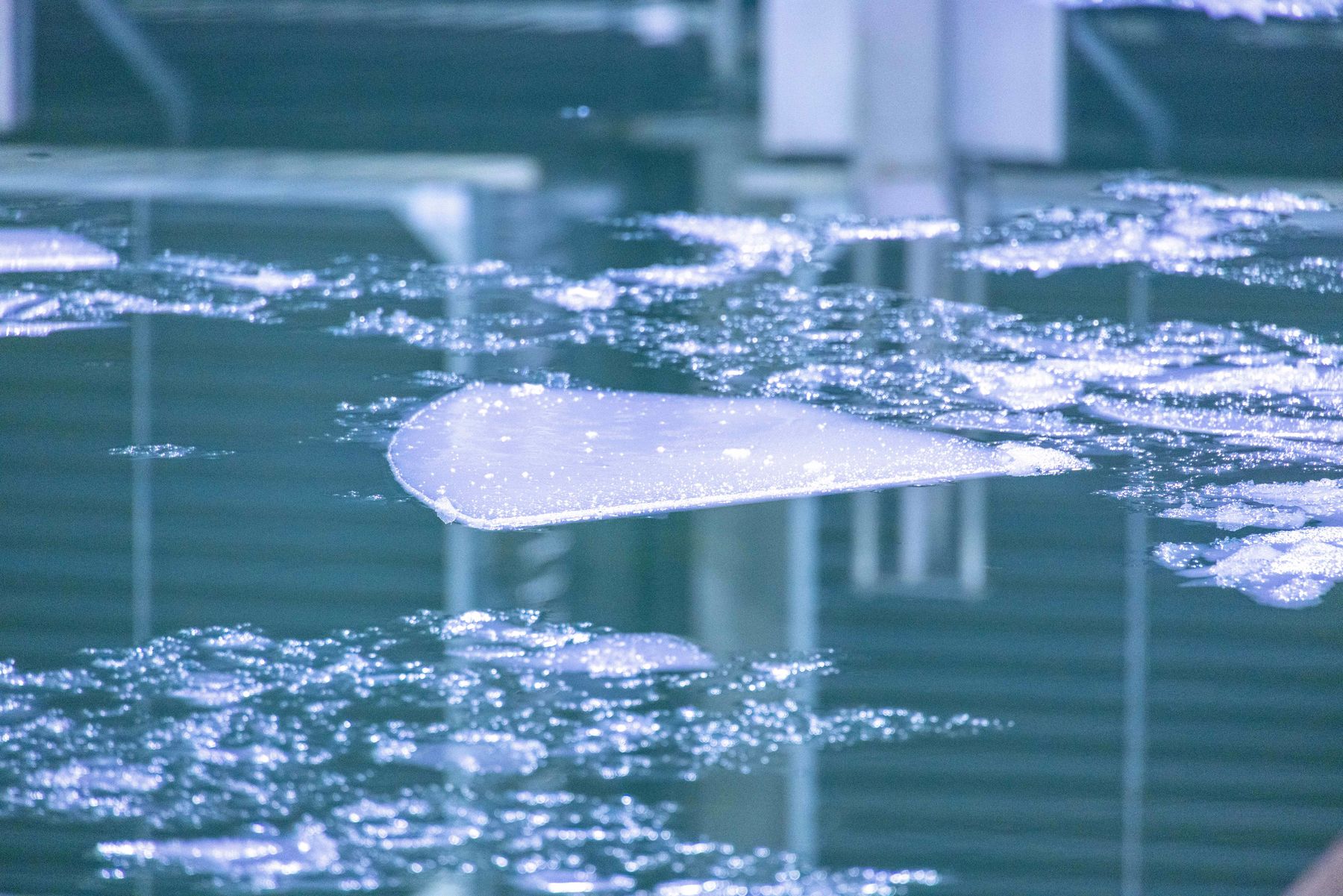

Unique ice testing tank

Finland is a global leader in arctic ship and marine technology, and the research carried out at Aalto University plays a crucial role in this. For instance, the Otaniemi campus is home to the world's largest indoor ice tank, the Aalto Ice and Wave Tank.

‘Our ice tank makes it possible to research both waves and ice at a smaller scale and create theoretical models for the interaction between them,’ says Jukka Tuhkuri, professor of arctic marine technology.

To tackle some of the more complex research problems, marine technology scientists are combining modern experimental research methods with artificial intelligence. ‘AI can analyse environmental data, vessel interactions and even people’s behaviour on-board,’ says Jani Romanoff, professor in marine technology.

There's also a desire to automate maritime traffic. Studies show that under normal conditions, a captain would be able to command about six ships simultaneously from an on-shore command centre. If remote control ships become the norm, seafaring work will have to expand to address IT questions related to information flow and the ability of intelligent systems to support decision-making in crisis situations.

The challenges of global seafaring are tackled in four research areas at Aalto University: Arctic Marine Technology, Advanced Structures, Hydromechanics, and Intelligent Marine Systems.

Text by Terhi Hautamäki